Delivering on distribution

November 27, 2023 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates

November 27, 2023 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Delivering on Healthcare Distribution

How to get healthcare to the people that need it

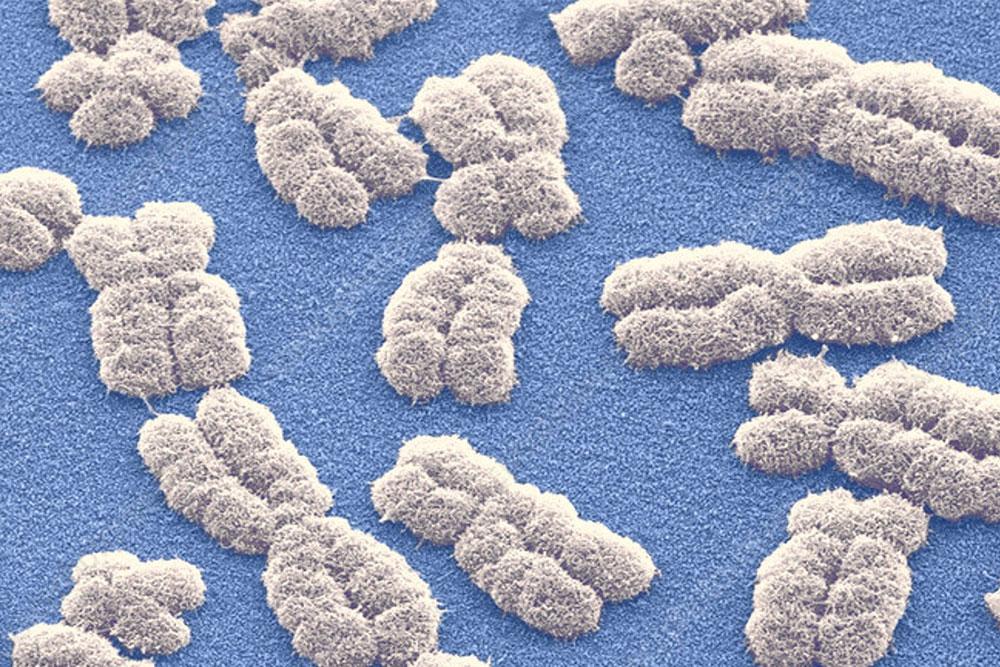

We are fortunate to live in an era of stunning medical achievements – breakthroughs which, just a generation ago, would have been hailed as near-miraculous. We have engineered effective treatments for HIV. We have developed targeted therapies, using stem cell and nanocarrier technology, to trace and destroy cancer cells in the body. We have built functioning bionic limbs for people blighted by accident or illness. We are, in short, becoming masters of our own medical destinies.

Yet sadly – some would say shamefully – these advances are not enjoyed equitably around the world.

While some health systems flourish, deep flaws in health supply chains are leaving many populations, particularly in the Global South, deprived of life-saving drugs and apparatus. What can we do to close this healthcare distribution gap?

Systemic symptoms of sickness

The World Bank recently noted that many low and middle-income countries (LMICs) are forced to rely on secondhand or outdated medicine to treat their sick.[1]

In Côte d’Ivoire, for example, more than one-in-ten HIV patients have had their combined anti-retroviral treatments (ARTs) interrupted due to lack of medicines, doubling the risk of death. Colombia, meanwhile, has experienced shortages of more than 200 different drugs across multiple disease areas. And in the Republic of Macedonia, around 30% of donated drugs were found to be out of date or on the cusp of expiring.

Within deprived countries, between 50% and 80% of medical equipment is deemed non-functional at any given time. The World Bank highlights one case in Mpumalanga, South Africa, where a patient suffering from a bleed almost died because the hospital ran out of tourniquets.

Other studies shed more light on the LMIC health imbalance. During a single year in Uganda, patients lost US$ 26.1 million on substandard or counterfeit antimalarials, either through direct costs or productivity losses due to illness and death. The poor were hit hardest, paying 12.1 times as much per capita for these inadequate treatments while dying at 12.7 times the rate of the wealthiest quintile. Rural communities registered almost 98% of deaths attributed to low-quality antimalarials.[2]

Similarly, in Nigeria, more than two-thirds of patients whose HIV treatment was interrupted due to supply shortages went on to develop resistance to vital ARTs as a result – as opposed to just 25% of those whose treatments continued unbroken.[3]

While many of us take the proximity of hospitals and clinics for granted, for families lacking motorized transport it is a very different story. Huge numbers of people around the world face more than a day’s walk if they need to reach a healthcare facility.[4] And if they do manage to arrive, will there be anyone to take care of them?

Not necessarily.

Vast regions of the Global South exist with fewer than one doctor per 10,000 people – a fraction of the expertise available in the developed world.[5]

Medical doctors per 10,000 people

Shortfalls in the global health pipeline are not just a matter of injustice or inequality – they are in many cases a matter of life and death.

The root cause of why life expectancies so starkly vary wildly, worldwide. The 10 nations with longest life expectancies include such mature economies as Hong Kong, Switzerland, Singapore and Italy, each recording 80+ lifespans. At the other end of the scale, the list of countries with the shortest lifespans is dominated by developing economies such as Chad, Nigeria, South Sudan and Somalia, all with life expectancies stuck in the 50s.[6]

Bridging the global healthcare gap by ensuring access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all, is one of the sub-targets of UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDGs) 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all, at all ages.

How has this unsustainable situation come to pass, and what can we do to correct it?

Diagnosing the distribution dilemma

At the heart of the problem lies a lack of understanding, and a corresponding lack of investment, in the discipline of healthcare supply chain management (SCM). SCM, in its optimal form, is a holistic top-down strategy, one incorporating every link in the healthcare distribution chain: Inventory management, sourcing, financing, quality control, warehousing, and eventual dispersal to clinics, pharmacies and hospitals worldwide.

In other words, getting the right drugs and equipment to the right people, in the right place and at the right time.

However, healthcare SCM in remote regions is traditionally beset by logistical barriers conspiring to undermine its efficiency:[7]

- Infrastructure: The shortage of modern healthcare clinics in rural areas hinders the distribution and storage of vital drugs, diagnostic kits and vaccines. Only costly infrastructure investment can reverse this situation – yet money is often in short supply.

- Location: It is not just medical supplies, but also trained personnel, that need deploying to communities in need. In rural areas, those remote from urban centers and lacking sophisticated transport links, delivering supplies and skilled specialists can pose a tough logistical challenge – especially if the terrain in question is expansive and largely undeveloped.

- Resource poverty: Healthcare facilities in remote locations commonly lack not only equipment and staff, but also finance. A shortage of funds prevents health planners in these regions from strategizing their way out of the healthcare quagmire. When unsophisticated infrastructure meets inferior technology, it can stymie the efforts of governments, health agencies and NGOs to improve logistics and overcome rural resource constraints.

- Inconsistent ‘cold chains’: A dependable and unbroken temperature-controlled supply line is vital for preserving organic products such as vaccines and plasma. However, impoverished areas often lack adequate refrigeration equipment, to say nothing of the reliable electricity sources needed to keep it operational.

- ICT: Poverty-hit areas are rarely blessed with the kind of effective information and communication technology (ICT) essential for any high-performance logistics network. Without supply chain tracking software, or up-to-date patient notes, healthcare distribution in developing regions is perpetually stuck in the slow lane.

In such a context, it is easy to understand how an international health crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic caused four deaths in the developing world for every fatality recorded in a wealthy nation, according to a report published by Oxfam.[8]

Are we really helpless to act in the face of such gross inequality?

Applying a technological tourniquet

With a vulnerable supply chain destabilizing the notion of equitable healthcare, attention turns to finding more efficient models of medical distribution.

How can we devise a fairer system in the face of stock shortages, price spikes, and dramatic peaks in demand such as pandemic response?

The first challenge is a shift in mindset. Instead of reacting to crises as they occur, we must proactively prepare for the risk of future shocks, such as climate change, another pandemic, geopolitical strife or natural disasters. The question is not simply whether one has enough resources for today, but whether one has enough resources to withstand an altogether less certain future.

Several solutions immediately present themselves. Investing in solar-powered chiller units, for example, can help maintain precious cold chains and make medicines last far longer during transit and storage. The value of solar refrigeration proved incontrovertible during the Covid era, when medicines were delivered to indigenous communities in off-grid areas across Africa, mitigating the virus’ impact among neglected households.[9], [10]

If modernizing and expanding a rural transport system proves unaffordable (or geographically impractical), innovative technologies such as drone delivery can nowadays form part of the solution. Drones have already been operating in the skies above Rwanda for six years, delivering blood and medical supplies to a dozen remote regional hospitals. Rwanda’s drone partner, Zipline, runs similar operations in Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria and the Ivory Coast, and aims to expand the number of hospitals it serves from 3,000 to 10,000 globally by the end of this year.[11]

Cost-effective measures such as cellphone apps and telemedicine software can simplify the logistics process by allowing remote consultations, treatment and monitoring. Investment in communications technology, such as universal broadband and 5G connectivity, can further support the rollout of healthtech to every doorstep.

Throughout the process of overhauling global healthcare distribution, three fundamental strategies should underpin our actions.

Firstly, ‘equitable healthcare’ as a concept must rise up the agenda worldwide.

Governments and the private sector alike must shift from a just-in-time mindset to a just-in-case alternative, with adequate supplies stockpiled to allow for sudden bursts of demand. All stakeholders in the medical supply chain must collaborate on this new vision of seamless medical distribution. Buyers should make ‘continuity of supply’ a primary evaluation criterion during tendering, and investors should make sustainable distribution a key boardroom goal.

Secondly, procurement models must gravitate away from single-source supply chains toward more diversified alternatives. This means manufacturers expanding their portfolio of raw material suppliers to safeguard against unintended disruptions. Likewise, it means hospitals and health services having deals in place with multiple manufacturers to bypass individual interruptions. Larger companies can collaborate on international technology transfers, sharing their practices with local manufacturers to help build capacity and grow stockpiles of medicines and vaccines regionally – much like the partnership approach to healthcare investment that guides Abdul Latif Jameel Health’s own activities in this vital area.

Thirdly, in an interconnected world, we must identify any weaknesses in global supply and distribution chains and work together to ensure continual care. From farmers growing the raw ingredients of medicines, to manufacturers of diagnostic tests wondering where a future pandemic will arise, to fleet operators sourcing the vehicles which will transport skills and supplies to far-flung locations – all need to coordinate on the common goal of logistical efficiency.

No government can force a change alone, and even in harmony they are limited by the vagaries of budgets and politics. The private sector is therefore integral to boosting medical resilience and ensuring the world truly delivers on the promise of fairer healthcare distribution.

Private sector prescribes a healthier outlook

Using the power and independence of our private capital, Abdul Latif Jameel Health has embarked on a number of initiatives with the potential to improve global healthcare distribution, particularly in the Global South.

In 2022, we signed a partnership agreement with Wellesta, a Singapore-based healthcare marketing and distribution company, to distribute advanced healthcare products throughout India. These products are designed to serve the diverse medical needs of more than 1.3 billion people across the country.

Recognizing the ongoing disparity in access to modern medicine, how else are we continuing our mission of accelerating healthcare across the Global South?

To help embed health inclusivity among the Global South, Abdul Latif Jameel Health has forged a new international commercial network spanning India, Kuwait, Morocco, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the UAE.

Under the deal, Abdul Latif Jameel Health-approved products will be distributed to hospitals, clinics and medical institutions, fast-tracking quality care within these communities. The international nature of the endeavor acknowledges the distinct commercial and cultural profile of each country. Only with our partners’ unique understanding of their individual markets can we align with the respective regulatory authorities for the services we are delivering.

Over the coming months, we are continuing to explore further partnerships and acquisitions within other important markets, and expect the network to expand across Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and Latin America.

“The worldwide health disparity risks leaving the Global South behind, yet this is a choice – a failure of imagination – rather than an inevitable consequence of geography,” says Akram Bouchenaki, Chief Executive Officer of Abdul Latif Jameel Health. “A joined-up distribution and logistics network demands equally joined-up thinking behind the scenes.”

“Mastering equitable health distribution means mastering the art of supply chain management and all that this entails: Diverse supply sources, robust transport links, cohesive local and regional strategies, bold private investment, and a spirited embrace of new technology.”

“We cannot allow the Global South, with its population of billions, its wealth of resources and its vast talent pool, to become diminished due to preventable healthcare shortfalls. One’s prospects should not be preordained by accident of birth. Whether ‘home’ is New York or Nigeria, San Francisco or Somalia, we all deserve an equal opportunity to lead a productive life.”

Maybe in a decade’s time we will be chronicling a Global South with a radically different health profile. One where HIV treatments are commonplace, modern diagnostics are breaking the stranglehold of cancer, and supportive equipment to overcome injury is readily available. The choice is ours.

[1] https://blogs.worldbank.org/health/tackling-health-care-supply-chain-challenges-through-innovations-measurement

[2] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31816072/

[3] https://aidsrestherapy.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12981-017-0184-5#Sec7

[4] https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-walking-only-map-of-travel-time-to-healthcare-without-access-to-motorized_fig4_344413291

[5] https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/medical-doctors-(per-10-000-population)

[6] https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/life-expectancy-by-country

[7] https://www.thehealthsite.com/diseases-conditions/logistics-challenges-in-rural-healthcare-how-to-bridge-the-gap-981762/

[8] https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/covid-19-death-toll-four-times-higher-lower-income-countries-rich-ones

[9] https://www.clasp.ngo/about/impact-stories/solar-powered-refrigerators-on-the-frontlines-of-off-grid-covid-19-response/

[10] https://internationalmedicalcorps.org/story/new-solar-fridge/

[11] https://impakter.com/how-drones-are-revolutionising-delivery-of-medicine/

Related Articles

For press inquiries click here, or call +971 4 448 0906 (GMT +4 hours UAE). For public inquiries click here.