Raring to go:

Confronting the challenge of rare diseases

August 9, 2023 | Dubai, UAE

August 9, 2023 | Dubai, UAE

Some diseases are so prevalent they have become familiar to everyone – think heart disease, cancer, diabetes and dementia, to name just a few. If you yourself are not one of the millions of sufferers worldwide, then chances are you have a friend of family member who is.

Yet many diseases – equally pernicious, equally devastating – slip under the radar because their incidence is relatively rare. Although definitions vary around the world, a disease is often classed as ‘rare’ if it affects fewer than 1 in 2,000 people, or less than 0.05% of a given population.

Lack of prevalence, needless to say, does not equate to lack of harm. Many rare diseases are life-limiting or result in a disproportionate chance of premature death. Tragically, one-third of children born with or developing rare diseases are destined to die before their fifth birthday. The occurrence of each individual disease might be uncommon, but collectively they impose a dramatic health burden on societies around the world.

Worldwide, at least 400 million people live with rare diseases, with many additional cases likely to go undiagnosed in poorer countries.[1] Since the list of rare diseases is so expansive – around 7,000 by some estimates – healthcare professionals frequently misinterpret the symptoms and fail to provide adequate treatment.

So, what do we actually mean when we describe something as a ‘rare disease’? The answer is far from straightforward.

Rare diseases are not one problem, but many

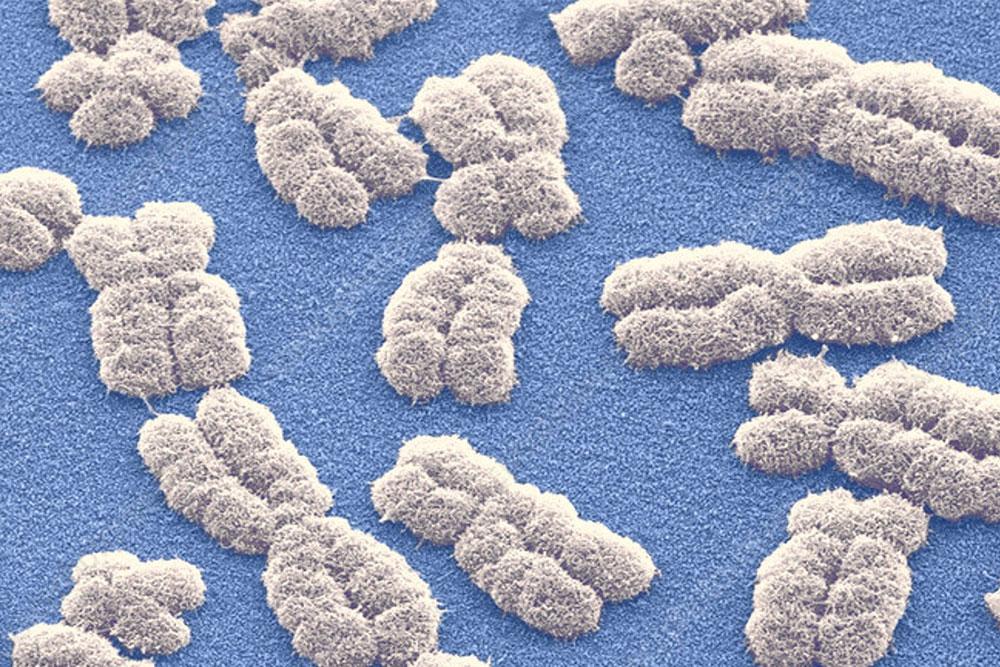

Rare diseases can include certain metabolic conditions, as well as particular cancers and auto-immune diseases. Many chronic genetic diseases also fall under the category of ‘rare’, several of which are incurable and strike in childhood, including cystic fibrosis, sickle cell, muscular dystrophy, spina bifida and hemophilia.

Yet ‘rare diseases’ have no unifying profile; the term in fact covers a diverse array of ailments, often contradictory in nature: [2]

- Some 72% of all rare diseases are genetic in origin. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, for example, characterized by progressive muscle degeneration, stems from a dystrophin gene mutation in 1 per 3,500 boys worldwide. In contrast, other rare diseases are triggered by infection. Onesuch case is Guillain-Barré Syndrome, a nerve condition causing weakness and pain, afflicting 1-2 in 100,000 people.

- Around 80% of rare diseases are inherited. Friedreich’s ataxia, for instance, affects around 1 in 30,000 Caucasians, causing slowed speech and walking difficulties and rendering most patients wheelchair-bound by middle age. Yet, other rare diseases are prompted by spontaneous genetic changes, such as Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva, (FOP) which causes the ossification of muscles and connective tissues in approximately 1 in 1 million people.

- Some rare diseases affect specific organs, while others are neurological in nature. Pseudomyxoma Peritonei, for example, is a rare (2 cases per 1 million people) cancer of the appendix; Tay Sachs disease, meanwhile, affecting 1 in 320,000 people, causes early onset mental degeneration.

- Some rare diseases are evident from birth, such as spinal muscular atrophy (affecting 1 in 100,000 people), its Type 1 variant causing death in infancy. Others only present symptoms in later life, such as Alkaptonuria (affecting cartilage, heart valves and kidneys, causing breathing difficulties) diagnosed in 1 in 250,000 people.

It is this complex web of causes, symptoms and prognoses that illustrates the challenge of combating rare diseases.

How rare disease patients slip through the system

Not much happens in our modern world without incentives – financial or otherwise. That is the way our systems and societies have evolved. The notion of value is the impetus for our collective progress.

For each individual disease classified as ‘rare’, with such a statistically small subset of patients, researchers can lack impetus to develop new medicines. As such, fewer than 5% of rare diseases currently have viable treatments.[3]

Typically, a rare disease patient waits four years for an official diagnosis, consulting with multiple doctors and receiving an average of three misdiagnoses in the interim.[4] Even after diagnosis, one-third of patients globally will not be able to access the treatment they need. And even where treatments for particular maladies do exist, they cost on average seven times more than treatments for common conditions.

In the most extreme scenarios, rare diseases fall into the category of ‘orphan diseases’. Some of these conditions are rare enough (fewer than 200,000 cases in the US) to be almost entirely neglected by drug developers. Examples include Fabry’s disease, in which the body’s enzymes cannot adequately process lipids, leading to heart attacks and strokes; and Alveolar Echinococcosis, caused by tumor-like tapeworm larvae growing in the liver.

Other orphan diseases end up overlooked because they are experienced predominantly in the developing world. We would potentially have far more potent weapons in our arsenals against Tuberculosis, Cholera, Typhoid and Malaria, if they were more prevalent in the world’s mature economic markets.

Such mundane realities highlight the geographic unfairness of the rare disease conundrum.

Rare diseases: A blight on the developing world

North African countries, notably, are undergoing what Sonia Abdelhak from the Institut Pasteur in Tunis describes as “an epidemiological transition”, with “non-communicable diseases such as deafness, blindness, oral diseases and certain genetic diseases increasing and becoming a public health priority”.[5]

The Middle East and Gulf Cooperative Council (GCC) region has its own particular rare disease landscape, exhibiting particular clusters of neuromuscular, metabolic and blood disorders.[6]

A higher-than-average proportion of consanguineous marriages, due to low population density, has led to disease spikes in certain Middle Eastern population groups.

In Oman, for example, one study showed that 229 out of 241 patients with inborn errors of metabolism were born to consanguineous parents. Around 1 in 10 Omanis are carriers of Sickle Cell and Beta Thalassemia.

Qatar, meanwhile, features a high instance of Homocystinuria, a serious condition leaving the body unable to process methionine, causing dangerous accumulation within the body.

Other genetic disorders occurring disproportionately throughout the region include Gaucher disease, Niemann-Pick disease A&B, Methylmalonic Aciduria, Propionic Aciduria and VLCADD, a rare genetic disorder of fatty acid metabolism.

Patients in the developing world are too often deprived of access to the best medicines – those dispensed routinely in wealthier economies.

Innovative gene therapies for spinal muscular atrophy, for instance, which can cost up to US$ 2 million per vial, are unavailable throughout Oman, Bahrain, Jordan and Egypt, despite being widely used in the West.

Efforts are under way to democratize access to rare disease treatments internationally. In Dubai, geneticists Dr Fatma Al Bastaki and Professor Fatma Al Jasmi have co-founded the UAE Rare Disease Society (UAERDS) with a broad range of goals: To increase awareness of rare diseases; to unite patients with appropriate healthcare professionals; and to provide financial support for families facing the burden of life-limiting conditions. They also promote premarital testing and newborn screening programs.

Screening programs have already demonstrated their value within the MENA region. One such scheme in Bahrain, for detection of Sickle Cell, has seen cases falls from 2.1% in 1985 to 0.9% now, with zero infant mortality.[7]

Such success stories are heartening given that overcoming the scourge of rare diseases means navigating an information deficit.

Knowledge sharing is key to long-term success

In the fast-evolving world of rare diseases, knowledge is power. Globally, more data must be collected to demonstrate the long-term economic benefits of combating, rather than neglecting, niche conditions.

Experts have called for a rare disease database at regional level to improve our understanding of prevalence. It is a simple step, but one that would encourage more risk-sharing research agreements between health authorities.

Pooling population-based genomic databases, such as the Saudi Genome Project and the UAE Genome Project, will help researchers and clinicians at the forefront of developing new treatments.[8]

This is especially urgent given the ethnic biases underpinning many current genome databases. As of 2016, just 19% of genome studies were based on populations of non-European ancestry. This was a marked improvement on past performance (as of 2009, for example, the figure was just 4%) but still highlights the limited scope of genomic technologies for tackling disease in the developing world.

How widespread is this rare disease burden? Considerable. In the Middle East alone, out of a total population of some 400 million, around 2.8 million people are known to have a rare disease.[9] Apart from the ongoing care costs associated with managing these conditions, the number represents a huge, missed opportunity in productivity terms, with such a high proportion of society left economically inactive.

Governments must be prepared to invest in solutions that do not necessarily produce direct or immediate results. They must adopt a future-focused mindset when supporting rare disease research and drug development – whether it be via grants, education investment, or a conducive legislative environment.

Prevention is almost always better than cure. By some estimates, an optimum approach would see around 80% of all rare disease investment directed towards prevention (early intervention, awareness and training) rather than pharmaceuticals.[10]

New tech rewriting the rulebook for rare diseases

With governments often sluggish to respond to the growing burden of rare diseases, it is increasingly the private sector that can help turn the tide, especially in the rapidly-advancing field of genetic therapies.

Advances in genomics and precision medicine are gradually allowing researchers to identify the causes of many rare diseases and unlock powerful therapies.

As of last year, more than 2,000 therapies based around tweaking the human genome were in development, with several promising ‘one-time lifelong cures’. By 2027 the market is expected to hit almost US$ 20 billion annually.[11]

Gene therapies are administered either in vivo (introducing molecular machinery into a patient’s body to genetically alter specific cells) or ex vivo (removing a cell, altering it genetically, then reintroducing it back into the patient).

The emergence of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology signifies a landmark moment in global efforts to interrupt the trail of destruction left by rare diseases.

NGS tools help radically accelerate a diagnosis by identifying the single gene which lies at fault – or even the specific characteristic of its malfunction.

NGS is proving a game-changer, not just for diagnosis but for the development of treatments too. Two recent examples show how detecting a culprit molecule has also helped indicate a promising remedy.[12]

- SLC18A2 was found to be the trigger gene for a childhood disorder characterized by poor movement control, mood disturbances and delayed development. This gene was known to encode a translocator of dopamine and serotonin into synaptic vesicles within neurons. Dopamine-based therapies therefore led to a decline in symptoms and resumption of regular body development.

- Riboflavin transporter genes SLC52A3 and SLC52A2 were pinpointed as the causes of Brown-Vialetto-Van Laere syndrome – deafness combined with ALS/Lou Gehrig’s Disease. Riboflavin-based treatments produced encouraging biomarker responses and patient outcomes.

Several thousand clinical trials for gene therapy treatments have been completed or are under way, with positive results noted across a range of disorders including metabolic, neurological, hematological and immunological conditions.

Genome-editing tools are showing particular promise, via technologies such as zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) systems. These engineered endonucleases introduce a ‘double-strand break’ to modify a DNA sequence, offering a precision technique for correcting unwanted genetic mutations.

Dubai-based Genpharm, is just one example of a private sector venture leveraging cutting-edge genetic technology to lead the fightback against rare diseases.

Genpharm is a specialty pharmaceutical company focusing on rare genetic diseases, orphan drugs and therapeutics. It provides its partners with fast-track market access and strategic advice across the MENA region.

Neutralizing the threat of rare diseases will require a global effort, one shared between innovation in the laboratory and bold vision within corridors of power. Public awareness is therefore as potent a weapon against rare diseases as any individual medicine.

Private sector contributes to global endeavor

After so long in the shadows, rare diseases are slowly attracting increased public attention. In December 2021, the UN moved to officially recognize “the need to promote and protect the human rights of all persons, including the estimated 300 million persons living with a rare disease worldwide” – with all 193 member states adopting the resolution known as PLWRD 2021.[13]

In so doing, the UN acknowledged a natural dovetailing between the concept of ‘universal health coverage’ and support for the rare disease community. Indeed, PLWRD 2021 reinforces Principle 2 of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, to “Leave no one behind”.

In Europe, the EU has launched a project to assist patients and families affected by rare diseases. The European Reference Network aims to unite those in need with expert information and treatment resources. More than 900 highly-specialist healthcare units now operate from around 300 hospitals across 26 member states. Consultations are carried out online through a clinical patient management system (CPMS), a software app allowing remote specialists to collaborate on real-time diagnoses and treatment plans for people with low-prevalence conditions.

Rare Disease Day, now an annual event, is observed on the last day of each February to improve medical representation for patients and their families.

By exposing the perils of misdiagnosis, treatment, inequality and isolation, it strives to improve access to diagnosis and therapies for anyone living with a rare disease.

This year’s Rare Disease Day, which took place at the end of February 2023, saw more than 600 events take place across 106 countries worldwide, including a Global Chain of Lights event involving schools, homes and workplaces joining the #LightUpForRare movement.

As we have seen with the efforts of Genpharm, it is the private sector’s patient, targeted capital that can help propel rare diseases up the global agenda.

“A disease’s rarity doesn’t lessen its impact to the sufferer,” says Akram Bouchenaki, Chief Executive Officer of Abdul Latif Jameel Health. “That is why we are partnering with organizations who share our vision of finding novel treatments for patients around the world, no matter their background, income or social status.

“By supplementing national health policies with ambitious research projects and energetic distribution models, we can help divert vital resources to people – and communities – too often hidden from global headlines.”

[1] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/03/rare-diseases-changing-the-status-quo/

[2] https://www.rarebeacon.org/rare-diseases/what-are-rare-diseases/

[3] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/03/rare-diseases-changing-the-status-quo/

[4] https://www.rarebeacon.org/rare-diseases/what-are-rare-diseases/

[5] https://twas.org/article/more-attention-rare-diseases-developing-countries

[6] https://edition.pagesuite-professional.co.uk/html5/reader/production/default.aspx?pubname=&edid=5632b0cc-5380-4577-99ca-6089409ace43

[7] https://edition.pagesuite-professional.co.uk/html5/reader/production/default.aspx?pubname=&edid=5632b0cc-5380-4577-99ca-6089409ace43

[8] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9632971/

[9] https://images.go.economist.com/Web/EconomistConferences/%7B757e740e-a8fe-457f-ae44-4938224f2ef0%7D_Rare_Diseases_roundtable_SummaryPaper_(2).pdf

[10] https://images.go.economist.com/Web/EconomistConferences/%7B757e740e-a8fe-457f-ae44-4938224f2ef0%7D_Rare_Diseases_roundtable_SummaryPaper_(2).pdf

[11] https://www.weforum.org/whitepapers/accelerating-global-access-to-gene-therapies-case-studies-from-low-and-middle-income-countries/

[12] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5815091/

[13] https://www.rarediseasesinternational.org/un-resolution/

Related Articles

For press inquiries click here, or call +971 4 448 0906 (GMT +4 hours UAE). For public inquiries click here.